A programme listener

is not particularly interested in the call letters or the frequency

of the station he is tuned to. A DXer, however, wants to fill in

the empty spaces of his logbook, perhaps in order to apply for a

QSL.

You do not have to master Spanish or Portuguese in order to enjoy listening to Latin

America, but distinguishing between the two languages is no doubt an

asset. So is of course the ability to distinguish between speech

accents, music and other features typical to certain areas of the

Western hemisphere.

Finding a new station, unlisted in the World Radio TV Handbook or one of the

principal listening reviews, is a most rewarding aspect of the DXing

hobby. A QSL stating “first report from abroad” is a showpiece

to strive for.

The aim of these notes is to give an outline of what

broadcasting in Latin America is all about. We will try to describe

it from various perspectives providing some tools towards

understanding what is being heard.

Technical points of interest, such as direction finding, greyline DXing at sunrise or

sundown, antennas etc. will not be covered

in this update to my book “Latin America by Radio”, which was

published in Finland in 1989.

For various reasons we will be devoting more attention to the Spanish speaking countries

of Latin America than to Brazil, where Portuguese is spoken, or to

areas in the Caribbean where English, French or Creole are the main

languages.

One obvious reason is that I have been living in a few Spanish-speaking Latin American

countries, notably Ecuador and Colombia. This also explains the

preponderance of recordings from these two countries.

The country abbreviations used are as follows:

A – Argentina, B –

Bolivia, Br – Brazil, C – Colombia, Ch – Chile, Cu – Cuba,

DR – Dominican Republic, E – Ecuador, G – Guatemala, H –

Honduras, M – Mexico, N – Nicaragua,

Pa – Panama, Pe –

Peru, Py – Paraguay, S – El Salvador, U – Uruguay, V –

Venezuela. |

THAT SPECIAL RING ABOUT LATIN AMERICAN BROADCASTING

We believe that

there are certain aspects of Latin American broadcasting that seem

special to DX-ers. Music is obviously one element, but there is also

something special about the way speakers, locutores, go about their

business. DXers may hate or love what they are hearing. Rarely, they

are left indifferent.

In an environment of noise and interference Spanish is perhaps

easier to understand than Portuguese. The traditional craftsmanship

of each country also plays an important role.

In certain countries, putting a person behind a microphone will not change his general

speech patterns. In others it does. In

Venezuela

and in Colombia,

a programme presenter, locutor, is required to pass pronunciation

and voice tests as well as tests of grammar and general knowledge.

Some programme hosts will make it a point to mention their license

numbers when signing on or signing off.

Again, in Venezuela and in Colombia, a programme host tends to

be more emphatic than

the man in the street. (1) To raise your voice is seen as important

when it comes to a sales pitch.

Stuttering commentators, especially on TV, will be

beset by mockery and ridicule from listeners and spectators.

Good enunciation pays off. Gustavo Niño

Mendoza, a newsreader on Caracol network, was designated the Number One newsreader in Colombia in

1987. Subsequently, he was given the honour of recording all of the

Caracol network station identifications.

In Venezuela, the Meridiano newspaper paid special tribute to the Radio Rumbos

newsreader Gilberto García

in an article for the 39thanniversary of the station in 1988.

While Europeans pay attention to written compositions, in Latin America rhetoric is by no

means frowned upon. This is perhaps why Scandinavian DXers get

impressed by Latin American speakers even without understanding what

is being said. Others may feel a bit uncomfortable with the fast

speech delivery of certain sports narrators, especially when

“cantando un gol”, singing a goal.

Whereas Colombians and Venezuelans seem to prefer emphatic speech in broadcasting, this

appears not to be the case in Bolivia, where up-tempo speech patterns

are rare in the broadcasting community. The catch is that messages

may miss the target, which was shown in a study by Javier Albó in

the 1970’s. His investigation concluded that 65% of commercials

and other announcements in radio went unnoticed by listeners.

In the 1970’s jingles may have been scarce in Bolivian broadcasting. Singing the

ads could have given a different result. Modern techniques in

attracting listeners´ attention in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and

Colombia do include

jingles,

but also a heavy dependency on

echo

chambers and reverb, not only for

advertisements, cuñas, but also for

station identification.

Another way of keeping listeners glued to the loudspeakers is the system used in Argentina

and Uruguay where male and female voices alternate in reading the

commercial spots (frases), sometimes mixed with occasional

pre-recorded stuff. We believe that this “dual” system of

adstrings (tandas publicitarias) is dynamic and that it enhances

listening.

In certain countries, alternating male and female voices may also appear on

devoted news channels such as Radio Reloj, in Cuba, and

Radioprogramas del Perú. No doubt the flow of news items tapped

from news wires will then become less monotonous, more vivid.

(1) Newsreader Cristóbal Américo Rivera is a medical doctor but he

has been reading the news in his particular way ever since the end of

the 1960´s on at least four different radio stations in Bogotá.

This recording is from Radio Reloj.

2. Decline of ShortWave Broadcasting in Latin America

In the early days of broadcasting, communication by road and air was

difficult or even non-existent. Shortwave broadcasting became a

useful means to bridge that gap. As telephone, cable and mail

services improved, shortwave has become less important as a means of

keeping people in the countryside in touch with the world.

The number of shortwave stations in Latin America has shrunk during the

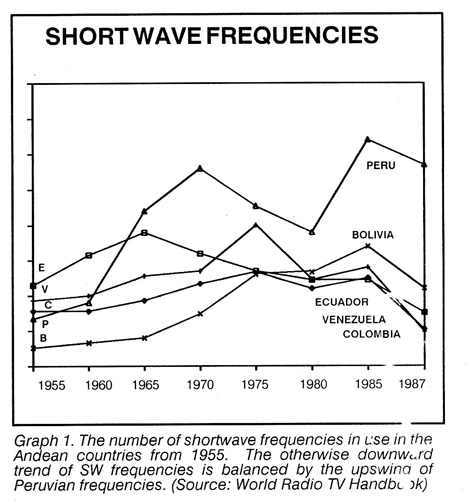

past few decades. This is shown by Graph 1,

which covers the principal Andean countries of South America.

In the early days of broadcasting, communication by road and air was

difficult or even non-existent. Shortwave broadcasting became a

useful means to bridge that gap. As telephone, cable and mail

services improved, shortwave has become less important as a means of

keeping people in the countryside in touch with the world.

The number of shortwave stations in Latin America has shrunk during the

past few decades. This is shown by Graph 1,

which covers the principal Andean countries of South America.

A peak ocurred in the 70’s, but since then the number of used frequencies

has been gradually dropping, except in Peru, where there has been a

continuous and uncontrolled growth of stations, some of which have

been operating without legal permits. (1)

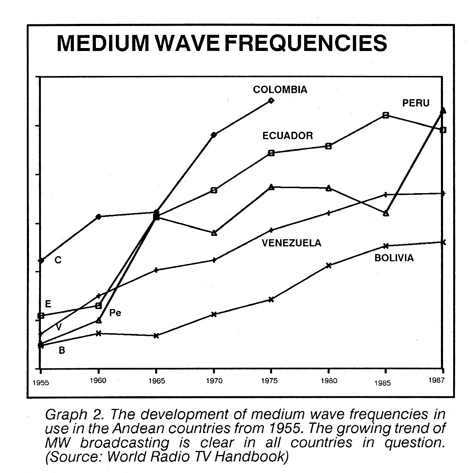

Graph 2 shows the continuous rise of medium wave operations in the same

countries. The number of FM transmitters has of course risen even

more steeply during the same period. (2)

|

In southern South America, including Brazil, there is a similar downward

turn for shortwave.

The trend appears to be irreversible, and it is believed that the number

of shortwave outlets will dwindle even further as TV, postal and

telephone services improve.

The shortwave operations in Latin America in 1989 were, in general,

geared for areas where other communications media were in an

underdeveloped state, mediumwave and FM transmissions missing.

This was one of the reasons for the upsurge of shortwave in the Peruvian

countryside in the 80’s. In Peru, and in Ecuador, at that time,

instant communication with distant and small places in the

countryside was best handled by means of shortwave.

DXers miss “the good old days” when there were many small Latin

American broadcasters on shortwave. Now that they are gone, we may

want to share the joy of those Latin Americans who probably feel that

they are now better served than before from a communications

viewpoint.

3. Broadcasting in Rural Areas When reliable ways of communication were absent, many people deemed it

practical to keep in touch with relatives and friends by means of

low-cost message services of shortwave radio.

In the 1980’s we monitored message programmes from stations in the

Ecuadorian, Peruvian and Bolivian jungle as well as the savannah

areas east of the Andean cordillera, but also from stations on the

Ecuadorian coastline, the southwestern part of Colombia, southern

Chile and in Paraguay. Less frequently such messages were also heard

on Argentine outlets in the interior.

Radio

Río Amazonas,

Radio

Iris and Radio Zaracay,

were typical examples of shortwave stations in Ecuador where you

would find message programmes.

In 2010, these three stations have been absent from shortwave for many

years. This confirms that message programmes were useful as long as

telephone lines were scarce. Now Ecuadorians, as most other Latin

Americans, can communicate with one another by way of cellphones, by

voice or text messages (mensajes

de texto).

In Bolivia most of the stations in the Beni used to carry message

programmes, for instance Radio Santa Ana with

its “Mensajero de la Mosquitania”, Radiodifusoras Trópico, with

its “Mensajero Tropical” etc .

In Peru, many stations in the Andean highlands offered the same kind

of service in Quechua or Aymara.

For a small medium wave station of, let’s say, 2kW power, daylight

reception is possible with a radius of some 20 to 30 km only. By

night, dependable reception is even more limited due to enhanced

long-distance reception, which will produce unexpected co-channel

interference.

If the station is very powerful and has a clear channel, a medium wave

frequency can be used for long-distance transmission of messages.

Radio Cristal, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, 870 kHz is one example. In Peru, Radio

Santa Rosa, 1500 kHz, and shortwave 6045 kHz, and in Chile,

Radio

Colo Colo, 1380 kHz.

Located in big capitals, these stations offered messages

from local listeners to their relatives living in the countryside.

Interestingly, Radio Cristal, which operates around the clock, had a widely listened-to message

slot just prior to sunrise, which is a suitable time for listening

(in the equatorial area you rise with the sun) as well as for

propagation. At that particular time medium wave is known to

propagate very far and with a minimum of fading.

Other early risers are the Paraguayans. Several stations carry mensajero

rural (rural messenger) programmes between 0500 and 0600 local time.

4. Broadcasters and Postal Services

In certain countries in Latin America, house-to-house delivery of

letters by a postman has been the privilege of those who were living

on the main avenues of the principal towns. Decades ago, many people

would pay for a Casilla or an Apartado at the Post Office instead of

having to queue in front of the Lista de correos desk to ask for any

letters.

For people with unknown addresses, letters could sometimes be sent in

care of someone with a well-known address, for instance a radio

station.

Radio Zaracay, in Ecuador, Radio Estrella Polar, in Peru, La

Voz de Samaniego, and

La

Voz de Anserma, in Colombia, are stations which in the past used to mention names of

people having letters to collect at the station.

There are countries possessing fast and reliable mail services, but, as a

rule, people may prefer to send important mail some other way,

preferably with a friend or a relative who is about to travel to the

same place. In several countries, local bus companies will carry

mail.

In Bolivia, people may choose to send their postal items via Flota

Copacabana coach. This bus company dumps the mail, not only parcels but also

plain letters, at each bus terminal along their routes.

In Colombia, where airmail was introduced in 1919, a private company,

Avianca, was in charge of all airmail, while

surface mail was handled by the state-owned Adpostal. Only stamps marked

“Aéreo” was accepted by Avianca. In 1966, coinciding with the

introduction of jetliners for national airmail,

Avianca offered an unusual special delivery service.

|

Letters posted

in Bogotá in the morning would be delivered to the addressee in any

of 20 major towns the same afternoon.

This service worked for some

time but is history now. The Colombian postal services has been

unified and the service is now more like “snail-mail”.

In Peru, at the turn of the 19th and 20th

century, a letter from the jungle town of Iquitos to Lima would

travel by boat down the Amazon river to the Atlantic port of Belém,

in Brazil, and thence to Liverpool in the UK from where it was sent

back to Lima via the Straits of Magellan (the southernmost tip of

South America)!

In general, it seems that letters from Europe to Latin America are

handled faster than those that have been mailed from a neighbouring

country. In 1966, letters from Sweden or Germany to Colombia would

arrive in 3 days, while letters from the UK and USA needed 5. A

letter from Colombia to Ecuador would also take up to 5 days.

Mail sent from Latin America to Europe

is slower. In the heydays of Avianca,

letters from Colombia to Sweden would arrive in 5 days. If

registered and sent by special delivery – via Paris – a letter

would make it in just 2 days!

Postage rates in 2010 are considerably higher from Latin America to Europe

than vice-versa. Broadcasting companies and other major companies in

Latin America have become heavily dependent on mail and package

delivery companies such as DHL, Fedex, UPS or their local

counterparts. The cost of renting a Casilla

or an Apartado has risen steeply in Latin America. In the 1960’s and 1970’s an

Apartado Aéreo was commonplace in Colombia, a Casilla

in Argentina. Today’s electronic messaging services are about to

convert P.O. Boxes into relics of the past.

5. Old and New Identification Patterns

CALL LETTERS

Pioneering broadcasters in Latin America were Radio Argentina (1920), Radio

Chilena (1922) and Radio México (1923). Available records do not

show that they were using call letters, which was a common practice

among stations in North America and Australia at that time.

As broadcasting stations proliferated international conventions were

agreed upon for allocation of frequencies and call letters . By the

end of the 20’s, call letters had been assigned to each country.

In Latin America, call letters became compulsory.

Shortwave listeners in the 30’s needed frequency tables with the

corresponding list of call letters in order to identify the station

and country they were receiving. The January 1934 issue of RADEX,

The All-Wave Radio Magazine, published at Mount Norris, Illinois,

contained a list of “the best” shortwave stations from various

countries.

With the proviso that radio telephone services perhaps are included in

this list, the 1934 survey of Latin America contained the following

number of entries:

| Argentina 19 |

Ecuador 5 |

| Bolivia 1 |

Brazil 7 |

| Guatemala 3 |

Mexico 10 |

| Colombia 14 |

Nicaragua 2 |

| Costa Rica 4 |

Panama 1 |

| Chile 4 |

Peru 3 |

| Dominican Rep. 3 |

Venezuela 23 |

Call letters, country and frequency were given for each station. given.

Many of these call letters (siglas

or indicativo) are familiar with us even today, CP5, HI1A, HC2RL, HCJB, TGW and

OAX4D.

In some countries, Colombia, Costa Rica and Venezuela, call signs were

similar to those assigned to today’s ham operators. This was, by

the way, also the case in many other countries, viz. USA, Canada,

Australia, Portugal and Spain.

First on shortwave from Venezuela was YV1BC, in Caracas. From the list one

cannot tell if the company name, Broadcasting

Caracas,, was used independently or in together with the call sign.

Nowadays, in Europe, none of the regular broadcasters are using call signs.

Spain was one of the last countries to abandon the use of their

EAJ, EAK, EFE and EFJ call letters well-known to European DXers in the

1960’s and 1970’s.

In Latin America, there are still a good many stations that display

their call signs in logos, and use them as part of their regular

station identification.

Newbies, however, seem to care less about call letters than the actual frequency on the AM or FM band.

Recently, with the upsurge of national networks, the “legal” identification

procedure will not always include a call sign, at least not at night

or during weekends. In Mexico, which is part of North America, it

still does. In Brazil it is also fairly common that the station, on

top of the hour, says, “Let’s pause for prefixos”,

which is what the call sign is being called in Portuguese.

PRONUNCIATION OF CALL SIGNS

The letters in the Spanish alphabet are not pronounced along identical

patterns in all countries. The letter Y, i griega

in Spain, is often ye in Latin America. In Portuguese it is rendered as ípsilõ).

Historically, B and V are pronounced the same way, either roughly as a B in English

or as an approach to a B, where the upper and lower lips fail to meet.

The uve for V in Spain, is nowhere to be heard in Latin America. The

labiodental V (which is the normal way of pronouncing it in English)

is a strange sound to native speakers of Spanish. People in

Argentina and Uruguay may use the labiodental V, supposedly due to

influence from Italian speech patterns.

(In the recorded ID for La

Voz de Carabobo it is impossible to distinguish between the V and the B in the call

sign YVLB. The Y is pronounced as ye).

W is seen as a foreign letter in Spanish. To some people it is doblebé

(or doblevé, which will be pronounced in the same way), others prefer dobleú.

(You may see the letter rendered in one word or in two). The international

La W network is referred to as la dobleú in all member countries excepting Chile, where it is mentioned as la

doblevé.

W is also extraneous to speakers of Brazilian Portuguese, who will use the English

pronunciation of the letter.

For figures is is convenient to remember that Brazilians often render the

figure 6 as méia (from meia dúzia, half a dozen).

Mentioning call letters as station identification is mandatory in North America,

which includes Mexico. In Central and South America this rule appears

to have been softened during the past few decades, one of the reasons

probably being the existence of nationwide networks in many

countries. Networks will break for station identification and local

advertisements only during the day, and not during weekends.

In old DX bulletins shortwave and medium wave information would refer to

the call letters and location only. QSLs were (and still are)

reported much the same way. Nowadays, the station name or slogan is

common. In a listing of frequencies, however, a station without call

letters will create an uncomfortable hiatus, and so bulletin editors

tend to supply at least the country identifier in order to fill the

empty space, for instance “HO---“ for Panama.

In the Swedish DX magazine Nattugglan

(No. 10, vol. 4, 1949) a listener writes: “On approx. 49.0 metres I

have been getting a station from Bogotá announcing ‘Cadena Radio

Colombiana’. Reception is quite good, despite severe interferences

at times. Which is their call sign?”

To be sure, he did not ask for the company name, just for the call sign.

In some countries, such as Colombia, the call sign is affixed to a

frequency, in others to a company.

In Ecuador, changing ownership would also imply a change of call

letters. The new call sign, shown on the company stationery, would

sometimes sport the initials of the owner’s name, or those of his

wife etc.

At Radio Guaranda, in Ecuador, we asked the owner, Sr. Jorge Carvajal, which were the

station call letters. The station was a newcomer, and in their

transmissions they did not mention any call sign at all. “Well”,

he said, “I don’t know but as we are in the 6thregion, so our callsign should of course be HC6JC”.

Thus he suggested J for Jorge and C for Carvajal.

The call letter issue, which still is very important to many DXers, does

not play any major role in Ecuador. not even with the licensing body,

IETEL (in 1987).

In an official list, published in the mid-80’s by the Ecuadorian government agency IETEL, there were three different

frequencies in the town of Guayaquil identified as HCDE2.

STATION NAMES, MONIKERS, SLOGANS

By the mid 50’s, judging from the same magazine, the Swedish

Nattugglan, the compulsory listing of call letters was gradually being expanded

to include a station name and/or a slogan.

This reflected a reality. Call letters were less often heard on the

air than the slogan.

Latins are prone to call their friends by nicknames, handles, and so the

habit of adding a moniker or a slogan to a call sign or to a

corporate name is quite normal. The idea is of course to create a

profile and an identity that listeners might feel comfortable with.

For AM and FM stations, which people would listen to in their cars, an

alpha-numerical identification pattern is very useful. Typically,

this pattern would indicate a frequency and an easily remembered

catch-word,

Valencia

12-20, on 1220 kHz,

Canal

115 – Radio Variedades, on 1150 kHz, Radio

Trece, on 1290 kHz, or Mara

Ritmo 900 AM.

Stations emphasizing a particular format will eventually have to change their

slogan – and jingle, if they have one - as they switch to another format.

In Mexico the old-timers on mediumwave, XEX, XEW, XEQ are known as “"la

X", "la W"

and “la Q”. The latter had a tropical format in the mid-80’s

and the station was then called la

Tropi-Q, a paraphrase of “trópico” (for “música tropical”).

Right now, in Lima, Perú, the letter Q, is a reference to the Colombian

“cumbia”, at least for listeners to a station on 1360 kHz,

frequently heard in Europe, and on107.1 FM, La

Nueva Q FM, donde manda nuestra cumbia.

Slogans are often ambiguous. The la ke buena

type of slogans common in Mexico (and the USA) carry the implicit

idea that the station is a woman.

The whistle heard in connexion with the Mexican Radio Mil identification refers to a woman, in this case

to ‘a whistling approval’ of a very beautiful woman in Mexico, Claudia Isla.

Half a century ago, in Latin American towns you would awake in the wee

hours of the morning by roving street vendors crying out the name of

the newspaper they were selling. With such an experience on your

mind you will easily accept the shouted presentation of news slots

such as "El

Reportero Caracol" with its slogan"el primero con las últimas"

(first with the latest news).

Now that roving news vendors are scarce and news is available anywhere,

any time, this would seem as an old-fashioned way of opening a

newscast.

Still the opening curtain for a programme is important,

and considerable thought is given to this detail.

The World Radio TV Handbook will give us access to call letters and

station names and only to a lesser degree to slogans and catchwords.

These are however worth keeping in mind as the identifier, if

correctly quoted in a reception report, provides good evidence of

actual reception.

Some slogans are elusive and changing, even with the season of the year.

In Colombia, this will happen as of November each year, when many

stations are gearing up for Christmas festivities, "En

Radio Santafé la música es de diciembre",

or "Radio Santafé", "la emisora de diciembre"

or "su

emisora de todos los diciembres.

Some stations will excel in slogans between music selections.

During a nighttime broadcast in 1971, Radio

Colosal, in Neiva, Colombia, on 4945 kHz, offered different slogans between

the musical selections, Esta es la jacarandosa alegría Colosal,

“colosal”, enormous, refers to the station itself and is also a

qualifier of “la alegría”, the joy, which is “jacarandoso”,

boisterous. This is a slogan where the station name is used in an

ambiguous way.

Some of the announcements are read by a DJ who is relatively tired as it

is at 3 a.m. The carted slogans are emphatic, trying to convey

emotion.

Colosal,

colosal, por ahí es la cosa, Colossal, enormous, that’s the word for it.

Radio Colosal, la llave grande para el progreso del sur de Colombia, key

to progress of southern Colombia.

Radio Colosal, imagen del Huila ante el mundo,

Huila in southern Colombia is the province, departamento,

where the station is located, and so Radio Colosal is conveying an

image of Huila to the world.

Radio Colosal, profesional is the common Todelar network ploy “somos profesionales”, we are

no amateurs, we are pros.

Radio Colosal, la emisora que sirve en el Huila

(“sirve” means that the station is a service institution that does its job well) Va

más lejos y siempre está en el corazón de los huilenses, the station reaches afar and yet it stays in the hearts of the people in

Huila.

Radio Colosal, calidad y capacidad certificadas por millares de oyentes,

thousands of listeners testify to the quality and professionalism of

the station.

Radio

Colosal distingue a quien la escucha, Radio Colosal is for truly discerning listeners or if you are not,

the stations programming will turn you into one.

Excepcional, colosal, por ahí es la cosa, Exceptional, colossal, that’s the Word for it.

STATION NAMES

When naming a radio station, the idea is to find a name which the intended

recognize as theirs. The name of a river or a mountain or some

historic person will serve as a catalyst for the targeted audience.

Without pretending to present an all-embracing list, we shall try to give

some station names sorted out by concepts.

When publishing my book in 1989 there was no such thing as Google or

Wikipedia. Now there is. It can be of wonderful help to us, now that

also pictures can be retrieved

when googling a concept.

In the following list you will find “Catatumbo”, “chasqui”, “Chinchaycocha”, “Ingapirca”

or “Tawantinsuyo”. Looking up any of these words from your

Google toolbar you will find not only more words but also pictures to explain their

meaning.

1. Present-day geographical names

|

1. Rivers |

2. Mountains,

volcanos |

3. Seas

and shores |

| Radio

Amazonas (E, Pe) |

Radio

Aconcagua (C) |

Emisoras

Atlántico (C) |

| Radio

Bío Bío (Ch) |

Radio

Altura (Pe) |

Radio

Litoral (V) |

| Radio

Huancabamba (Pe) |

Radio

Cordillera (C) |

Radio

Pacífico (C) |

| Radio

Mira (C) |

Radio

Illimani (B) |

Ondas

del Caribe (V) |

| Radio

Pastaza (E) |

Radio

Los Andes (Pe, V) |

Ondas

del Mar (V) |

| Radio

Utcubamba (Pe) |

Radio

Macarena (C) |

Ondas

de los Médanos (V) |

| Ondas

del Huallaga (Pe) |

La

Voz del Galeras (C) |

La

Voz de la Costa (C) |

| Ondas

de Mayo (C) |

La

Voz del Tolima (C) |

La

Voz del Litoral (E) |

| Ondas

del Meta (C) |

Ondas

del Chimborazo (E) |

|

| Ondas

del Sinú (C) |

Ecos

del Cayambe (E) |

|

| Ondas

del Yaque (DR) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Apure (V) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Cinaruco (C) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Guaviare (C) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Napo (E) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Río Cauca (C) |

|

|

| La

Voz del Upano (E) |

|

|

| Ecos

del Atrato (C) |

|

|

| Ecos

del Combeima (C) |

|

|

| Ecos

del Orinoco (V) |

|

|

| Ecos

del Torbes (V) |

|

|

|

1.5 Lakes |

1.6 Other

geographical features

|

1.7 Geographical

coordinates |

| La Voz del Atitlán (G) |

Radio

Altiplano (B) |

La

Voz del Centro (C) |

| Radio

Chinchaycocha (Pe) |

Radio

Cataratas (A) |

La

Voz del Norte (C) |

| Ondas

del Titicaca (Pe) |

Radio

Chaco Boreal (Py) |

La

Voz del Trópico (B) |

| |

La

Voz de Ciénaga (C) |

Voces

de Occidente (C) |

| |

La

Voz de la Sabana (C) |

Radio

El Sur (Pe) |

| |

La

Voz de la Selva (Pe, C) |

|

| |

La

Voz del Valle (C) |

|

| |

La

Voz del Llano (C) |

|

| |

Radio

Pampas (Pe) |

|

| |

Radio

Patagonia Chilena (Ch) |

|

| |

Radio

Vega (DR) |

|

|

|

|

|

1.8 Flora

and faun

|

1.8.1 Animals

|

1.8.2 Trees,

plants |

| |

Radio

Cardenal (V) |

La

Voz de la Caña (C) |

| |

Radio

Colibrí (C) |

Armonías

del Palmar (C) |

| |

Radio

Delfín (C) |

Brisas

del Palmar (C) |

| |

Radio

El Cóndor (B) |

Radio

Sarandí (U) |

| |

Radio

Estrella del Mar (Ch) |

|

2. Names of historic interest

|

2.1 Greek

and Latin heritage |

2.2 Precolumbian

(mythological, geographical,

cultural) |

2.3 Famous

indigenous men living prior

to colonization or during the Independence

period (also eponyms)

|

| Radio

Amazonas (E, Pe) |

Radio

Chimú (Pe) |

Radio

Amauta (Pe) |

| Radio

Apolo (V) |

Radio

Chortís (G) |

Radio

Atahualpa (Pe) |

| Radio

Atenas (E) |

Cadena

Cuscatlán (S) |

Radio

Caupolicán (Ch) |

| Radio

Atenea (CR) |

Radio

Eldorado (C) |

Radio

Colo Colo (Ch) |

| Radio

Atlántida (E, Pe) |

Radio

Guaraní (Py) |

Radio

Huancavilca (E) |

| Radio

Cáritas (Py) |

Estación

Wari (Pe) |

Radio

Lautaro (Ch) |

| Radio

Concordia (Pe) |

Radio

Inca (Pe) |

Radio

Rumichaca (E) |

| Radio

Cronos (Ch, E) |

La

Voz de Ingapirca (E) |

Radio

Zaracay (E) |

| Radio

Eco (C, B, M) |

Radio

Tupac Amaru (Pe) |

|

| Radio

Fénix (U) |

Radio

K’echí (G) |

|

| Radio

Iris (E) |

Radio

Liribamba (E) |

|

| Radio

Nueva Esparta (v) |

Radio

Machu Picchu (Pe) |

|

| Radio

Sténtor (B) |

Radio

Maya (G) |

|

| Radio

Titania (CR) |

Radio

Paitití (B) |

|

| La

Voz de los Centauros (C) |

Radio

Pajatén (Pe) |

|

| |

Radio

Panzenú (C) |

|

| |

Radio

Qollasuyo (Pe) |

|

| |

Radio

Quisqueya (DR) |

|

| |

Radio

Tawantinsuyo (Pe) |

|

|

2.4 Famous

men of European descent living

during the Independence period and

later (eponyms)

|

2.5 Battlefields

from Independence period and

later

|

2.6 Other

politically inspired names |

| Radio

Anzoátegui (V) |

Radio

Ayacucho (Pe) |

Radio

Batallón Colorados (B) |

| Radio

Artigas (U) |

Radio

Frente Sur (N) |

Radio

Batallón Topáter (B) |

| Radio

Agustín Aspiazu (B) |

Radio

Junín (Pe, V, C) |

Radio

Democracia (E) |

| Radio

Presidente Balmaceda (Ch) |

Radio

Pancasán (N) |

Radio

Granma (Cu) |

| Radio

Batlle y Ordóñez (U) |

Radio

Sipe Sipe (B) |

Radio

Insurrección (N) |

| Radio

Belalcázar (E) |

La

Voz del Carabobo (V) |

Radio

Libertad (B, C, Ch, E, Pe, V) |

| La

Voz de Benalcázar (C) |

|

Radio

Patria Libre (C)Radio

Paz (N) |

| Radio

Belgrano (A) |

|

Radio

Rebelde (Cu) |

| Radio

Bolívar (C, E, V, Pe) |

|

Radio

Revolución (Cu) |

| Radio

Camargo (B) |

|

Radio

Soberanía (Ch) |

| Radio

Presidente Castilla (Pe) |

|

Radio

Triunfo (C, Pe) |

| Radio

Nacional Espejo € |

|

Radio

Trinchera Antiimperialista (Cu) |

| Radio

Presidente Ibáñez (Ch) |

|

Radio

Venceremos (S) |

| Radio

Valentín Letelier (Ch) |

|

La

Voz de las Fuerzas Armadas (DR) |

| Radio

El Libertador (U, V) |

|

La

Voz del Poder Popular (N) |

| Radio

Carlos Antonio López (Py) |

|

|

| Radio

Martí (USA) |

|

|

| Radio

Mitre (A) |

|

|

| Radio

Monagas (V) |

|

|

| Radio

Morazán (H) |

|

|

| Radio

O’Higgins (Ch) |

|

|

| Radio

Padilla (B) |

|

|

| Radio

General Pico (A) |

|

|

| Radio

Portales (Ch) |

|

|

| Radio

Riquelme (Ch) |

|

|

| Radio

Rivadavia (A) |

|

|

| Radio

Rivera (U) |

|

|

| Radio

Sandino (N) |

|

|

| Radio

Libertador (San Martín) |

|

|

| Radio

San Martín (Pe, A) |

|

|

| Radio

Sarmiento (A) |

|

|

| Radio

Sucre (E, V) |

|

|

| Radio

Inés de Suárez (Ch) |

|

|

|

2.7 “Remember

the day” |

2.8 Religious |

2.9 Other

names with religious onnotations

|

| |

2.8.1 Names (Eponyms) |

|

|

Radio

2 de Febrero (B)

|

Radio

Jesús del Gran Poder (E)

|

Radio

Avivamiento (C, Pa)

|

|

Radio

Primero de Marzo (Py)

|

Radio

Juan XXIII (B)

|

Radio

Baha’i (Ch, E, B, Pe)

|

|

Radio

16 de Marzo (B)

|

Radio

León XIII (ch)

|

Radio

Buenas Nuevas (G)

|

|

Radio

23 de Marzo (B)

|

Radio

Loyola (B)

|

Radio

Fuego del Espíritu Santo (B)

|

|

Radio

1 de Mayo (H)

|

Radio

María (many countries)

|

Radio

Luz y Vida (E)

|

|

Radio

18 de Mayo (B)

|

Radio

María Auxiliadora (B)

|

Radio

Paz y Bien (E)

|

|

Radio

9 de Julio (A)

|

Radio

Pío XII (B)

|

Radio

Renuevo (DR)

|

|

Radio

9 de Julho (Br)

|

Radio

San Gabriel (B)

|

Radio

Revelación (DR)

|

|

Radio

19 de Julio (N)

|

Radio

San Ignacio (B, Pe)

|

Radio

Verbo (Pa)

|

|

Radio

13 de Octubre (N)

|

Radio

San José (B)

|

La

Voz Evangélica (H)

|

|

Radio

11 de Noviembre (E)

|

Radio

San Miguel (B, Pe)

|

Faro

del Caribe (CR)

|

|

Radio

21 de Diciembre (B)

|

Radio

San Miguel Arcángel (Pe)

|

Ondas

de Luz (CR) |

|

Radio

26 (Cu)

|

Radio

Santa María (Ch) |

|

| Radio

27 de Diciembre (B) |

|

|

|

2.10 Stars and celestial phenomena |

|

|

|

Radio

La Cruz del Sur (B)

|

Radio

Estrella (C, Pe)

|

Radio

Sideral (E)

|

|

Radio

Catatumbo (C, V)

|

Radio

Estelar (E, V)

|

Radio

Satélite (Pe, V)

|

|

Radio

Relámpago (H)

|

Radio

Estrella del Sur (Pe)

|

Radio

Galáctica (E, M)

|

|

Radio

El Sol (C, E, V)

|

Radio

Estrella Polar (Pe)

|

Radiodifusora

Galaxia (B)

|

|

Radio

Luna (C)

|

Radio

Estrella Maya (M)

|

Radio

Constelación (H)

|

|

Radio

Star (Pe)

|

La

Voz de las Estrellas (C)

|

Radio

Cosmos (B, Pe) |

|